Not many people actually get to meet their hero.

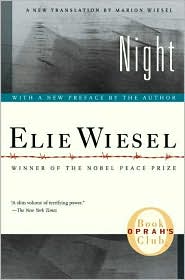

Last night, I got to meet mine. You see, there's this man named Elie Weisel. He's a Holocaust survivor and a Nobel Peace Prize winner. His memoir Night tells of the year he and his father spent in the concentration camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald, the names of two places I wish I didn't know.

I've been teaching his book to sophomores for the last six years. I know it so well that I sometimes think I can tell you on which page you can find Moishe the Beadle or the gold tooth or the injured foot or the incredible death march at the end. Weisel made it out alive; his father did not.

So my good friend Debbie called me earlier this week and said that she had two tickets to see Elie Weisel speak; did I want one?

Yes. Yes I did.

So Debbie picked me up and on our way to Saint Xavier University where he was speaking, we talked about how neither one of us could let ourselves believe this week that we were actually going to see him. I had to keep pretending that it might not happen just so I could contain myself. I'm not kidding. I'm that neurotic.

Debbie got us seats in the VIP section (she's got connections) and we waited. Of course we were there an hour early so we had quite a long time to wait, but we needed to be there that early. It was Elie Weisel. He survived the holocaust.

My sister-in-law Vivian sent me a text. She said she'd been talking to Elie and he thought we should come over afterwards to drink sangria.

Debbie said, "Well, he survived the holocaust. We should listen to him."

The three of us managed to get over our nervousness with shop talk until someone finally came to the stage. Of course, they spent about ten minutes on introductions and honorary doctoral degrees (the man's got to have at least two hundred thousand of those) and then Elie Weisel began to speak.

The three of us managed to get over our nervousness with shop talk until someone finally came to the stage. Of course, they spent about ten minutes on introductions and honorary doctoral degrees (the man's got to have at least two hundred thousand of those) and then Elie Weisel began to speak.

Of course, genius me hadn't thought to bring any paper. I mulled over this for a while while Elie spoke about Cain and Abel. Why did the Bible start with such a dark story? he asked us. Two men in all the world, brothers, and one kills the other. Why would this be the first story we hear after creation? Perhaps, he said, perhaps it is because anytime we kill, we kill our brother.

Of course, genius me hadn't thought to bring any paper. I mulled over this for a while while Elie spoke about Cain and Abel. Why did the Bible start with such a dark story? he asked us. Two men in all the world, brothers, and one kills the other. Why would this be the first story we hear after creation? Perhaps, he said, perhaps it is because anytime we kill, we kill our brother.

It's the kind of hilarity that arises when you're nervous and giddy and can't wait for something to happen. The man in front of us turned around. He was a teacher, too, he said. What did we teach? Debbie said she taught eighth grade and they bonded over their mutual love for middle school.

The three of us managed to get over our nervousness with shop talk until someone finally came to the stage. Of course, they spent about ten minutes on introductions and honorary doctoral degrees (the man's got to have at least two hundred thousand of those) and then Elie Weisel began to speak.

The three of us managed to get over our nervousness with shop talk until someone finally came to the stage. Of course, they spent about ten minutes on introductions and honorary doctoral degrees (the man's got to have at least two hundred thousand of those) and then Elie Weisel began to speak.He's a little guy, and spry, with an excellent Einstein look to his full head of hair. He wore a tailored velvet jacket and spoke with an accent that wasn't German but sounded a little like it, not French either but sounded a little like that too. I was instantly enamored of him, and could see me making a fool of myself over him. Seriously. He's got sex appeal. Are you allowed to say that about Elie Weisel? Are you even allowed to think it? I mean, the man's got the kind of stature that few can equal. The Dalai Lama, maybe. Yes.

I took out my cell phone and zoomed in as close as I could and snapped a picture. Of course it turned out blurry, but I'm posting it anyway, because it's my picture of the day I saw Elie Weisel.

He began to speak, and as he spoke, I began to repeat sentences to myself so that I could remember them later. The longer he spoke, however, the more sentences I repeated until I knew I could never possibly remember them all. That's when I began digging in my purse for my pen.

Of course, genius me hadn't thought to bring any paper. I mulled over this for a while while Elie spoke about Cain and Abel. Why did the Bible start with such a dark story? he asked us. Two men in all the world, brothers, and one kills the other. Why would this be the first story we hear after creation? Perhaps, he said, perhaps it is because anytime we kill, we kill our brother.

Of course, genius me hadn't thought to bring any paper. I mulled over this for a while while Elie spoke about Cain and Abel. Why did the Bible start with such a dark story? he asked us. Two men in all the world, brothers, and one kills the other. Why would this be the first story we hear after creation? Perhaps, he said, perhaps it is because anytime we kill, we kill our brother.I held my breath as I heard this. This I would remember.

Finally I came to a realization: the back of my ticket was blank. I furiously scribbled the things I could remember. I've forgotten so much. I wish I could tell you everything he said, but I'll content myself with what I did manage to walk away with.

He began to speak of the Bible. God's only mistake in writing the Bible, he said, was in not getting copyright. He could have been a millionaire many times over.

Yes. Elie Weisel is funny. I didn't expect that one, either.

He then recounted a conversation he'd had with a friend. Who is the most tragic figure in the Bible? the friend asked him.

Abraham, because God asked him to kill his only son? But no. Not Abraham.

Isaac, because his own father stood over him with a knife, ready to kill him? But no. Not Isaac.

What about Moses, who was alternately loved and hated by both God and his people his whole life? But no. Not Moses either.

The most tragic figure in the Bible is God.

No human being is alone; only God is alone.

Since he was speaking at a Catholic university, he spoke at length about the relations between Catholics and Jews. Then he told a story about Pope John the XXIIIrd. He had a friend, you see, a Jewish friend, who came to him one day and said do you have any idea what the Catholic liturgy actually says about the Jews? And the Pope said no, and they examined it together, finding anti-Semitic statements everywhere. And do you know what that Pope did? He changed the liturgy. Anyone who's Catholic knows what a big deal that is.

I certainly had no idea.

Then he spoke about my cousin, Pope John Paul II. (He's a third or fourth cousin; I'm not kidding.) He spoke about how John Paul invited a rabbi over every week to study the Bible together and promote dialogue between the faiths. Relations between Catholics and Jews have never been better than they are today, Weisel told us. He only made one mistake: he should have invited a Muslim, too.

This sent him into a discussion on hatred. Hatred is always born of fanaticism, he said. And fanaticism, whether political or religious, has always been the author of the worst things we've ever done to each other. It's when religious fanaticism is married to political fanaticism that things get really dangerous.

You see, a fanatic by his very nature negates the idea of dialogue. He says to himself that only he has God's ear. And if he truly believes that, what can I do, what can anyone do to convince him?

He makes God his accomplice.

That one nearly knocked the breath out of me. I wish I could retell it with the same eloquence.

He didn't spend a lot of time talking about the Holocaust. He said only a few things. Why, in all that he went through, did he never lose his faith?

A heart that is broken is the most whole.

A faith that is wounded is the most pure.

The question is not how remarkable it was that he survived. It is how remarkable it was that he retained his sanity. And he did that by turning to study. He's a professor of Judaic studies, you know.

Another, that if he carries any anger over what happened, it is that people knew, and they didn't warn them. They had a maid who brought them food at night in the ghetto. She snuck in and risked her life and said that if they wanted to hide in the mountains, they could stay in her little hut. The Nazis were not penetrating that high ground. They would have been safe.

But his father did not know. They listened to the radio at night and never once in all over their speeches did Roosevelt and Churchill say to the Jews of Eastern Europe what was happening at Auschwitz. Nobody told them to stay away from the trains. And get this: the Russians were only thirty kilometers away. That's eighteen miles. Eighteen miles to safety.

But people were indifferent. They were insensitive to what the ramifications of not speaking would be. Insensitivity, he said, is the biggest sin of all.

He spoke of Joseph at the bottom of the pit, surrounded by snakes and scorpions and crying for his life. His brothers threw him into that pit and then went to have dinner. A feast. They were insensitive to his cries for help. It is the darkest moment in all the Bible, he said. It is because they were insensitive to what they were doing to him.

Insensitivity is never an option.

This, by the way, is the part of his speech where he made me want to be better. He said that people are always feeling shame that they are hungry. That is wrong. We should be ashamed that they are hungry.

Insensitivity is never an option.

When someone is suffering, we may not be able to do something to end their suffering -- the AIDS patient who is going to die regardless, for instance -- but we can be with them. We can be sensitive to what they are going through. We can say to them, I cannot save you, but I think of you.

Insensitivity is never an option.

Did I mention that I got to meet him? I shook his hand and my mind went blank. All the things I wanted to tell him about how important his book was to me left me and all I could do was say how very pleased I was to meet him. He smiled and gently clasped my hand. We posed for a picture with the photographer and someday I'll show it to my grandchildren. That's the day I met Elie Weisel, I'll say.

2 comments:

wow.

I'm impressed and envious and think I will print this out to share some time if I ever get to teach this book.

xxx

I come back and read this because I love this day. I love that you shared it with me. We are teachers, and we're talking about God.

Post a Comment