So I take her to a bar on the north side, a hole-in-the-wall neighborhood joint in Wrigleyville (go Cubs!) called Trader Todd's where they sing bad karaoke every night of the week and it isn't long before she tells me she doesn't like it. And it's not just because she's a White Sox fan. I'm a little surprised because I'm feeling rather comfortable at this bar, but she says no. None of these people are talking to us.

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it the superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides: Time makes more converts than reason. Thomas Paine, Common Sense

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

I've got madd skills, yo

So I take her to a bar on the north side, a hole-in-the-wall neighborhood joint in Wrigleyville (go Cubs!) called Trader Todd's where they sing bad karaoke every night of the week and it isn't long before she tells me she doesn't like it. And it's not just because she's a White Sox fan. I'm a little surprised because I'm feeling rather comfortable at this bar, but she says no. None of these people are talking to us.

Monday, April 21, 2008

Tiny Miracles

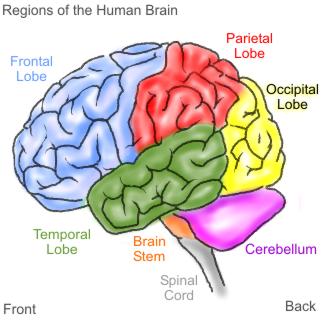

Sometimes I feel like I'm a brain expert after all the learning we've done since my nephew was first conceived. Anyway, when Drew was only a few weeks in the womb, they did an ultrasound and found an anomaly in his brain. Soon after, they sent my sister in for an MRI and took pretty detailed pictures of his entire brain. After that, he was diagnosed with Dandy Walker syndrome, which basically means that he was missing certain parts of his brain (the vermis, which connect one hemisphere to the other) and others were VERY underdeveloped (the cerebellum, which basically controls motor function). Those things would be problems his whole life, they said. She would just have to find a way to work around them, and no one had any idea what this would mean.

Sometimes I feel like I'm a brain expert after all the learning we've done since my nephew was first conceived. Anyway, when Drew was only a few weeks in the womb, they did an ultrasound and found an anomaly in his brain. Soon after, they sent my sister in for an MRI and took pretty detailed pictures of his entire brain. After that, he was diagnosed with Dandy Walker syndrome, which basically means that he was missing certain parts of his brain (the vermis, which connect one hemisphere to the other) and others were VERY underdeveloped (the cerebellum, which basically controls motor function). Those things would be problems his whole life, they said. She would just have to find a way to work around them, and no one had any idea what this would mean.

At the time, my sister's only reaction was this: whatever it is, I don't care as long as the baby lives. She could deal with anything except losing him.

When he was born, they performed another MRI to the same basic results. The only difference was that they saw the vermis did exist; they were just few and underdeveloped. The neurologist said that from this point forward, we would just have to play a waiting game. We went in for checkups. He was poked and prodded, and made to sit up just to see which way he'd fall and if he'd try to correct himself. The doctor gave us recommendations: we could work with him this way and that to see if we could make him burn the necessary neuropathways that would help him function somewhat normally.

How to describe my sister during all this? A mama bear. She worked his limbs, over and over. She was told he wouldn't understand music, but she played it for him constantly in the hopes that another part of his brain would learn to love it. She made him stand; she made him sit; she made him do things that other "normal" babies weren't doing at that developmental point. She was going to do every thing she could to make sure that her baby, no matter what his problems, would develop as close to normally as possible.

Now, I have other nieces and nephews. They all started walking at different times, but with Drew, they warned us that it might be a good long time before he started walking. However, about a month before his first birthday, my sister and I were playing with him, sitting a few feet apart from each other and helping him practice his balance. "Let go," she told me. "Watch." And then, he stood, all by himself. Mary smiled and said, "Come to Mama." And do you know that little boy walked? Eleven months old, missing a major part of his brain, and walking.

Since then, he's been something of a holy terror, running around the house like Godzilla. They weren't quite prepared for how quickly he was going to be moving, in fact.

Enter my brother-in-law. He's a good guy, and tries to do his part to share in the childcare. My sister went to volunteer in her daughter's classroom one day, and Tom was left alone with the baby. He put Drew in one of those walkers, and Drew was running happily all over the floor. That baby was fast. So fast, in fact, that when Tom ran downstairs to get something and didn't close the door all the way, Drew grabbed the handle, pulled it open and went tumbling down the stairs. (Men.)

Now, you'd think a spill down the stairs wouldn't be a happy ending to a story, but when they rushed him to the hospital, they decided to do another MRI to check for a concussion. They got the results back: no concussion, and no stitches needed. He was relatively unscathed, considering the tumble he'd taken. Oh. He sported a nice black eye for about a week.

But here's the kicker: Mary looked at the MRI results and saw a difference. Things that weren't there when he was born were there. They told her this was impossible, but she showed the films to me and I, too, saw the difference. Even to my untrained eye, it looked significant. They'd told us it was impossible, but it really looked different to us. I was almost afraid to hope.

She called the neurologist and made an appointment. When she told him what she thought, he looked at her with pity, because of course, he thought it was impossible that there would be a change. But there was. The vermis, which at first had seemed nonexistent and then underdeveloped were now normal size. And the cerebellum, which had been totally underdeveloped, had grown to almost normal size on one side. The other side is still underdeveloped, but the doctor said that likely his brain would figure out a way to compensate.

It seems his brain already has compensated, because when he's unhappy, the only thing that will make him happy is music, the very thing they said he wouldn't appreciate. He's got great taste, too. His favorite videos are the Muppets. For Christmas, I found a Kermit doll on ebay. Now that he's walking, he carries it around with him.

In short, our beautiful baby boy has a much brighter future than we'd originally thought. He might never play baseball, but hey. Maybe he might. Miracles do happen. He is, I think, proof of that.

Monday, April 14, 2008

ALHOP

To say that I loved these books doesn’t quite do the feeling I had for them justice. I would read these books over and over again. When my parents would yell at me that it was time to turn out the light and go to bed, I’d huddle under the covers with a flashlight and read, again, about nasty Nellie Olsen or Lazy, Lousy Liza Jane. And because they were so important to me, I was obsessed with what they must have looked like. I’d study the front of the books and Garth Williams’s illustrations inside.

It was my Laura Ingalls fix, and I watched every minute even though I knew that half the stuff they showed on television never happened in real life. They never had an adopted brother named Albert, for instance. However, as time wore on and the girls grew older, that’s where the books stopped and the tv series continued. I couldn’t separate fact from fiction any longer. Did Mary really marry another blind man and found a new school for the blind? I didn’t know. I hoped so, because I really wanted Mary to end up happy. And I wondered. Everything there was to know about this family I wanted to know.

Now, this was in the days before the internet and you couldn’t just find these things out. You had to go to the library and actually do some research. And lo, though I was a somewhat lazy kid, I did find a few things. The trouble was, the Hazel Crest Public Library wasn’t exactly teeming with information on the Ingalls family.

But I grew up, as people do, and my obsession for Laura went the way that children’s obsessions often go. That is, until Dawn and I took a trip to the Ozarks last week and saw along the way a tiny sign off US 60. That sign said "Wilder Family Home."

I knew immediately what it was. I turned to Dawn. I couldn’t help myself. Oh my god, I said. It’s Laura Ingalls Wilder’s home.

And really, if I’d thought about it before we took the trip, I would have known that it was there, because I read the book where Laura and Almonzo take their wagon and drive from Desmet, South Dakota to Mansfield, Missouri to start an apple farm. I did know that. I did. But I was surprised by the reality of it nonetheless.

And the reason that Dawn is my best friend is that she immediately responded, "Well, we have to go."

And we really did. Have to go, that is. Dawn understood this by taking just one look at me. You see, this was my somewhat-forgotten childhood dream.

The old homestead is a tiny white house on the top of the hill. When you climb the hill, you enter through a small museum. And the first thing you encounter, the thing that I needed to see more than anything, were the pictures.

Standing in the back row are Carrie, Laura, and baby Grace. Seated are Ma, Pa, and Mary, Laura’s blind sister. I stood in front of the photograph and studied it a good long while. Christina, my niece, stepped up beside me. I pointed to each picture and explained who they were. I’m sure she didn’t understand why I knew so much or even why I thought they were so important, but she listened patiently. "Look at Mary," I said. "She how she’s not looking at the camera? That’s because she’s blind."

And I couldn’t believe that I was actually looking at Mary. And Laura. And all the rest of them. I mean, check out Pa’s crazy beard. He looked nothing, I mean nothing, like Michael Landon.

But then, I saw something even better: Pa’s fiddle.

I walked around it about ten times. I’d never studied a Picasso the way I studied this fiddle.

She didn’t look like Melissa Gilbert, either, but oh, was she Laura. See that determined look in her eye? That girl could kick some major ass if she wanted to.

Now, besides Laura, I had a pretty major crush on Almonzo. I’m sure it started with the actor that they got to play him on the television series:

But the photo archives had the photo I’d been longing to see: the real Almonzo. And girls, he’s just as pretty in real life:

The rest of the museum had artifacts, like the jewel box Laura was given that one Christmas in Walnut Grove (I remembered that) or the writing desk where they found the hundred dollar bill that they thought they’d lost (I remembered that like I’d read it yesterday), or the clock that Almonzo (sigh) gave Laura on their second anniversary.

I remembered it. I remembered every word. I could hardly contain my memories.

We took a tour of their little house. Almonzo had built the entire thing for Laura, starting with one room and adding each additional room as they could afford it. The floors were covered with linoleum. I couldn’t get over that. They’d lived in that house until the early 1950s, you know.

We got to the end of the tour and the rest of the people filed out. I stopped to speak with my guide. She was of an age where she’d have known Laura, but just barely. She’d been a very young woman when Laura died at the age of ninety. I asked her about this Lane fellow. Whatever happened to him?

Lane, for those of you who aren’t insane like me, is the man that Laura’s daughter Rose married.

She leaned in. "Well," she said. "He was in real estate. Rose met him in San Francisco. They were married for nine years and," she paused dramatically, dropping her voice to almost a whisper, "then they divorced."

I gasped. She seemed to expect it. Rose never had any children, she said, so Charles Ingalls’s direct line died out completely. Of the girls, only Carrie ever married, to a man who had two stepchildren. That meant that Mary’s husband on the show was entirely fictional.

I was sad for Mary, and surprised at Carrie. She seemed like such a sour woman in that photograph.

And so there I was, finally separating fact from fiction, and wishing a little that the fiction had been the truth. I didn’t want to think of Pa’s girls as anything less than happy.

Then I stepped out on the porch with the kids and Dawn took our picture.

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

Hot For Teacher

"So. What do you do for a living?"

It's gotten so I consider lying, just so I don't have to deal with what will inevitably follow.

You see, I'm a teacher.

I mean, I guess I understand. We were the instruments of your adolescent torture. We made you sit in your desks when you wanted to stand and told you to keep your mouth shut when you wanted to talk. You all dealt with it in different ways. Some of you wrote nasty things on your desk about us. Some of you muttered angry things behind our backs. And some of you? Some of you just sat back and imagined us naked.

There's a huge subculture of this teacher fetishization. I get it. The only trouble is, it turns you into slavering idiots the minute you find out what I do.

Response 1: The repressed masochist. You immediately shiver and say, "Ooh, teacher! Will you punish me?"

Gee, I've never heard that one before. But yes, come here so I can punish you just for being stupid. I'll even wear my porn star outfit while I do it.

No. I spend day after day in my classroom looking at the same kids every day and I never teach them anything. They're lucky if I teach them how to read.

Of course I think I reach them, otherwise I couldn't stand the job for more than a week. They wouldn't let me.

Response 3: The cynic. You look at me and smile a very nasty smile. You think I'm in this job because I'm not smart enough or too lazy to do anything else, and you think I don't work hard enough. "So you took this job because of summers off, huh?"

Yes, that's precisely why I took this job. Because it's so easy. No, really. You should see me in my classroom. I just sit down and chat with the kids and it's all so lovely and soon it's June and I'm in my bathing suit down on the beach. I know you're still slaving away in your office in your wool suit and I laugh at you, sucker.

The thing that kills me is that 95% of the men who take that tone with me would get ripped to shreds by my kids. I don't teach in one of those fancy, clean private schools. I'm in the inner city, and my kids are dealing with the stuff you see in the movies every day. The only trouble is, it isn't the movies. It's life. And when they die, they really die. So shut up, asshole. The minute you can tell me that one of your coworkers got knifed in an alley or his head blown off by a ten-year-old, then maybe you can talk to me about summers off.

Response 4: The guy who actually knows teachers. "Tough job. You like it? You going to stick with it?"

Yes, probably.

But this guy at this particular party? He was an amalgamation of 1, 2, and 3. I answered his questions politely and then escaped to another room. Because I never say these things out loud. Only in my head.

If you really want to know the truth, I blame Van Halen.