So I take her to a bar on the north side, a hole-in-the-wall neighborhood joint in Wrigleyville (go Cubs!) called Trader Todd's where they sing bad karaoke every night of the week and it isn't long before she tells me she doesn't like it. And it's not just because she's a White Sox fan. I'm a little surprised because I'm feeling rather comfortable at this bar, but she says no. None of these people are talking to us.

Perhaps the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor; a long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it the superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides: Time makes more converts than reason. Thomas Paine, Common Sense

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

I've got madd skills, yo

So I take her to a bar on the north side, a hole-in-the-wall neighborhood joint in Wrigleyville (go Cubs!) called Trader Todd's where they sing bad karaoke every night of the week and it isn't long before she tells me she doesn't like it. And it's not just because she's a White Sox fan. I'm a little surprised because I'm feeling rather comfortable at this bar, but she says no. None of these people are talking to us.

Monday, April 21, 2008

Tiny Miracles

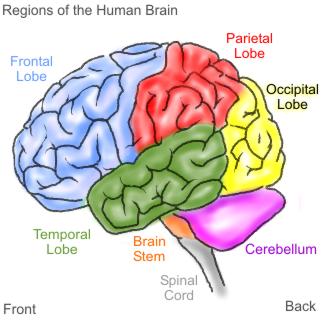

Sometimes I feel like I'm a brain expert after all the learning we've done since my nephew was first conceived. Anyway, when Drew was only a few weeks in the womb, they did an ultrasound and found an anomaly in his brain. Soon after, they sent my sister in for an MRI and took pretty detailed pictures of his entire brain. After that, he was diagnosed with Dandy Walker syndrome, which basically means that he was missing certain parts of his brain (the vermis, which connect one hemisphere to the other) and others were VERY underdeveloped (the cerebellum, which basically controls motor function). Those things would be problems his whole life, they said. She would just have to find a way to work around them, and no one had any idea what this would mean.

Sometimes I feel like I'm a brain expert after all the learning we've done since my nephew was first conceived. Anyway, when Drew was only a few weeks in the womb, they did an ultrasound and found an anomaly in his brain. Soon after, they sent my sister in for an MRI and took pretty detailed pictures of his entire brain. After that, he was diagnosed with Dandy Walker syndrome, which basically means that he was missing certain parts of his brain (the vermis, which connect one hemisphere to the other) and others were VERY underdeveloped (the cerebellum, which basically controls motor function). Those things would be problems his whole life, they said. She would just have to find a way to work around them, and no one had any idea what this would mean.

At the time, my sister's only reaction was this: whatever it is, I don't care as long as the baby lives. She could deal with anything except losing him.

When he was born, they performed another MRI to the same basic results. The only difference was that they saw the vermis did exist; they were just few and underdeveloped. The neurologist said that from this point forward, we would just have to play a waiting game. We went in for checkups. He was poked and prodded, and made to sit up just to see which way he'd fall and if he'd try to correct himself. The doctor gave us recommendations: we could work with him this way and that to see if we could make him burn the necessary neuropathways that would help him function somewhat normally.

How to describe my sister during all this? A mama bear. She worked his limbs, over and over. She was told he wouldn't understand music, but she played it for him constantly in the hopes that another part of his brain would learn to love it. She made him stand; she made him sit; she made him do things that other "normal" babies weren't doing at that developmental point. She was going to do every thing she could to make sure that her baby, no matter what his problems, would develop as close to normally as possible.

Now, I have other nieces and nephews. They all started walking at different times, but with Drew, they warned us that it might be a good long time before he started walking. However, about a month before his first birthday, my sister and I were playing with him, sitting a few feet apart from each other and helping him practice his balance. "Let go," she told me. "Watch." And then, he stood, all by himself. Mary smiled and said, "Come to Mama." And do you know that little boy walked? Eleven months old, missing a major part of his brain, and walking.

Since then, he's been something of a holy terror, running around the house like Godzilla. They weren't quite prepared for how quickly he was going to be moving, in fact.

Enter my brother-in-law. He's a good guy, and tries to do his part to share in the childcare. My sister went to volunteer in her daughter's classroom one day, and Tom was left alone with the baby. He put Drew in one of those walkers, and Drew was running happily all over the floor. That baby was fast. So fast, in fact, that when Tom ran downstairs to get something and didn't close the door all the way, Drew grabbed the handle, pulled it open and went tumbling down the stairs. (Men.)

Now, you'd think a spill down the stairs wouldn't be a happy ending to a story, but when they rushed him to the hospital, they decided to do another MRI to check for a concussion. They got the results back: no concussion, and no stitches needed. He was relatively unscathed, considering the tumble he'd taken. Oh. He sported a nice black eye for about a week.

But here's the kicker: Mary looked at the MRI results and saw a difference. Things that weren't there when he was born were there. They told her this was impossible, but she showed the films to me and I, too, saw the difference. Even to my untrained eye, it looked significant. They'd told us it was impossible, but it really looked different to us. I was almost afraid to hope.

She called the neurologist and made an appointment. When she told him what she thought, he looked at her with pity, because of course, he thought it was impossible that there would be a change. But there was. The vermis, which at first had seemed nonexistent and then underdeveloped were now normal size. And the cerebellum, which had been totally underdeveloped, had grown to almost normal size on one side. The other side is still underdeveloped, but the doctor said that likely his brain would figure out a way to compensate.

It seems his brain already has compensated, because when he's unhappy, the only thing that will make him happy is music, the very thing they said he wouldn't appreciate. He's got great taste, too. His favorite videos are the Muppets. For Christmas, I found a Kermit doll on ebay. Now that he's walking, he carries it around with him.

In short, our beautiful baby boy has a much brighter future than we'd originally thought. He might never play baseball, but hey. Maybe he might. Miracles do happen. He is, I think, proof of that.

Monday, April 14, 2008

ALHOP

To say that I loved these books doesn’t quite do the feeling I had for them justice. I would read these books over and over again. When my parents would yell at me that it was time to turn out the light and go to bed, I’d huddle under the covers with a flashlight and read, again, about nasty Nellie Olsen or Lazy, Lousy Liza Jane. And because they were so important to me, I was obsessed with what they must have looked like. I’d study the front of the books and Garth Williams’s illustrations inside.

It was my Laura Ingalls fix, and I watched every minute even though I knew that half the stuff they showed on television never happened in real life. They never had an adopted brother named Albert, for instance. However, as time wore on and the girls grew older, that’s where the books stopped and the tv series continued. I couldn’t separate fact from fiction any longer. Did Mary really marry another blind man and found a new school for the blind? I didn’t know. I hoped so, because I really wanted Mary to end up happy. And I wondered. Everything there was to know about this family I wanted to know.

Now, this was in the days before the internet and you couldn’t just find these things out. You had to go to the library and actually do some research. And lo, though I was a somewhat lazy kid, I did find a few things. The trouble was, the Hazel Crest Public Library wasn’t exactly teeming with information on the Ingalls family.

But I grew up, as people do, and my obsession for Laura went the way that children’s obsessions often go. That is, until Dawn and I took a trip to the Ozarks last week and saw along the way a tiny sign off US 60. That sign said "Wilder Family Home."

I knew immediately what it was. I turned to Dawn. I couldn’t help myself. Oh my god, I said. It’s Laura Ingalls Wilder’s home.

And really, if I’d thought about it before we took the trip, I would have known that it was there, because I read the book where Laura and Almonzo take their wagon and drive from Desmet, South Dakota to Mansfield, Missouri to start an apple farm. I did know that. I did. But I was surprised by the reality of it nonetheless.

And the reason that Dawn is my best friend is that she immediately responded, "Well, we have to go."

And we really did. Have to go, that is. Dawn understood this by taking just one look at me. You see, this was my somewhat-forgotten childhood dream.

The old homestead is a tiny white house on the top of the hill. When you climb the hill, you enter through a small museum. And the first thing you encounter, the thing that I needed to see more than anything, were the pictures.

Standing in the back row are Carrie, Laura, and baby Grace. Seated are Ma, Pa, and Mary, Laura’s blind sister. I stood in front of the photograph and studied it a good long while. Christina, my niece, stepped up beside me. I pointed to each picture and explained who they were. I’m sure she didn’t understand why I knew so much or even why I thought they were so important, but she listened patiently. "Look at Mary," I said. "She how she’s not looking at the camera? That’s because she’s blind."

And I couldn’t believe that I was actually looking at Mary. And Laura. And all the rest of them. I mean, check out Pa’s crazy beard. He looked nothing, I mean nothing, like Michael Landon.

But then, I saw something even better: Pa’s fiddle.

I walked around it about ten times. I’d never studied a Picasso the way I studied this fiddle.

She didn’t look like Melissa Gilbert, either, but oh, was she Laura. See that determined look in her eye? That girl could kick some major ass if she wanted to.

Now, besides Laura, I had a pretty major crush on Almonzo. I’m sure it started with the actor that they got to play him on the television series:

But the photo archives had the photo I’d been longing to see: the real Almonzo. And girls, he’s just as pretty in real life:

The rest of the museum had artifacts, like the jewel box Laura was given that one Christmas in Walnut Grove (I remembered that) or the writing desk where they found the hundred dollar bill that they thought they’d lost (I remembered that like I’d read it yesterday), or the clock that Almonzo (sigh) gave Laura on their second anniversary.

I remembered it. I remembered every word. I could hardly contain my memories.

We took a tour of their little house. Almonzo had built the entire thing for Laura, starting with one room and adding each additional room as they could afford it. The floors were covered with linoleum. I couldn’t get over that. They’d lived in that house until the early 1950s, you know.

We got to the end of the tour and the rest of the people filed out. I stopped to speak with my guide. She was of an age where she’d have known Laura, but just barely. She’d been a very young woman when Laura died at the age of ninety. I asked her about this Lane fellow. Whatever happened to him?

Lane, for those of you who aren’t insane like me, is the man that Laura’s daughter Rose married.

She leaned in. "Well," she said. "He was in real estate. Rose met him in San Francisco. They were married for nine years and," she paused dramatically, dropping her voice to almost a whisper, "then they divorced."

I gasped. She seemed to expect it. Rose never had any children, she said, so Charles Ingalls’s direct line died out completely. Of the girls, only Carrie ever married, to a man who had two stepchildren. That meant that Mary’s husband on the show was entirely fictional.

I was sad for Mary, and surprised at Carrie. She seemed like such a sour woman in that photograph.

And so there I was, finally separating fact from fiction, and wishing a little that the fiction had been the truth. I didn’t want to think of Pa’s girls as anything less than happy.

Then I stepped out on the porch with the kids and Dawn took our picture.

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

Hot For Teacher

"So. What do you do for a living?"

It's gotten so I consider lying, just so I don't have to deal with what will inevitably follow.

You see, I'm a teacher.

I mean, I guess I understand. We were the instruments of your adolescent torture. We made you sit in your desks when you wanted to stand and told you to keep your mouth shut when you wanted to talk. You all dealt with it in different ways. Some of you wrote nasty things on your desk about us. Some of you muttered angry things behind our backs. And some of you? Some of you just sat back and imagined us naked.

There's a huge subculture of this teacher fetishization. I get it. The only trouble is, it turns you into slavering idiots the minute you find out what I do.

Response 1: The repressed masochist. You immediately shiver and say, "Ooh, teacher! Will you punish me?"

Gee, I've never heard that one before. But yes, come here so I can punish you just for being stupid. I'll even wear my porn star outfit while I do it.

No. I spend day after day in my classroom looking at the same kids every day and I never teach them anything. They're lucky if I teach them how to read.

Of course I think I reach them, otherwise I couldn't stand the job for more than a week. They wouldn't let me.

Response 3: The cynic. You look at me and smile a very nasty smile. You think I'm in this job because I'm not smart enough or too lazy to do anything else, and you think I don't work hard enough. "So you took this job because of summers off, huh?"

Yes, that's precisely why I took this job. Because it's so easy. No, really. You should see me in my classroom. I just sit down and chat with the kids and it's all so lovely and soon it's June and I'm in my bathing suit down on the beach. I know you're still slaving away in your office in your wool suit and I laugh at you, sucker.

The thing that kills me is that 95% of the men who take that tone with me would get ripped to shreds by my kids. I don't teach in one of those fancy, clean private schools. I'm in the inner city, and my kids are dealing with the stuff you see in the movies every day. The only trouble is, it isn't the movies. It's life. And when they die, they really die. So shut up, asshole. The minute you can tell me that one of your coworkers got knifed in an alley or his head blown off by a ten-year-old, then maybe you can talk to me about summers off.

Response 4: The guy who actually knows teachers. "Tough job. You like it? You going to stick with it?"

Yes, probably.

But this guy at this particular party? He was an amalgamation of 1, 2, and 3. I answered his questions politely and then escaped to another room. Because I never say these things out loud. Only in my head.

If you really want to know the truth, I blame Van Halen.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

Wisconsin: An Introduction

Some kvetchers have been complaining that I haven’t written anything lately. Well, it’s because I’ve been sad. And sick. And when that happens, I can’t write a word. Not one that anyone wants to read, anyway. I’m going to warn you right now: you may not want to read this. Especially those of you who think that my little notes are something of a trainwreck. This is the trainwreck extraordinaire, methinks. So. Fair warning.

I remember when I was in grad school, I took a class on nonfiction. I was really excited about the class: the whole thing was reading essay after essay and trying to write essays of our own. No research papers. Just nonfiction. I was so pleased. The first class, the professor read my essay out loud. The next class, we had to read an essay that excerpted the book Prozac Nation. I read the essay, and thought, yes. I can write about sadness and depression and drugs and the things they do to your brain.

So I poured my heart into this little essay. I told about Wisconsin and shopping at the Piggly Wiggly and how it made me want to drive my car into the nearest streetlamp. I told about depression and getting treatment and how drugs didn’t really help when the problem was you.

I wrote this thing, I turned it in, and I waited for him to choose me again. Except, this time, he didn’t read my essay. Instead he handed it back with a gigantic B emblazoned on the top with the comment, and I’ll never forget this, Depression just isn’t funny. Find something new to say or move on.

I wanted to kick him. I wanted to take my essay, rip it into 623 pieces, and sprinkle it over his receding hairline. If life were just like the movies, I would have done all of those things. Instead, I did none of these things. The next week, I wrote a new essay. This time it was about being a woman. I talked about my experience with inequality at a job I had with a manly man company and I tried to say something funny. He wanted funny. This time, again he gave me a B. His comment: Don’t get so emotional. It’s just not interesting.

It’s just not interesting.

Now, I wish I could tell you that this man pushed me hard through the rest of the semester to turn out something new and splendiferous, but I can’t tell you that. I wrote a few good essays, I wrote a few mediocre ones. By the end of the semester, his scathing commentary led me to despise him. He was a misogynist, I told myself. He hated depressed people. He hated people from Chicago. He hated me.

Of course he didn’t. He didn’t care about me one way or another. He probably never thought about me for more than the two minutes it took for him to skim over my essays. I was just another writer in a pile of writers who knew how to string a few words together in a readable way but not, unfortunately, in an enjoyable one. It’s taken me a couple of years to realize that I was sitting in a class taught by a curmudgeonly old man who was telling me precisely what any journal’s editor would tell me upon reading my essays. It doesn’t matter if I put my heart into it. It only matters if people want to read it.

And depression just isn’t funny. He’s right, the motherf*cker.

Okay. But. I’ve been in the depths of it. I remember one year when I was supposed to be in college but instead spent all my days sleeping until three o’clock. I failed all my classes but one. When the semester ended and summer started, I lay in wait for the mailman. For months, I hadn’t been able to get out of bed before three, but now I stalked the mailbox from noon until five. And I was victorious. I got my report card. My parents couldn’t understand why they hadn’t seen it. Oh, I said. I got it. I did fine.

I’d turned into a brilliant liar. Or maybe not so brilliant. They wanted to believe me.

Eventually, I dropped out of school and got a job. A few years went by before it hit me that badly again. By then, I’d moved to Wisconsin. Nobody could believe I’d done it. Wisconsin, land of the cheeseheads? Once, not long after I moved there, my friend Tim wrote me an email with the subject line: Cheeses of Nazareth. The message said only, what is this place, the promised land?

No.

But the subject line was funny, and for the next couple of years we kept it. We’d exchange emails two and three times a day and sometimes I couldn’t tell which Cheeses of Nazareth I was answering.

I can always tell when my mood is at its lowest when I start to make Macaroni and Cheese. I once told a roommate of mine in college that it was one of my favorite foods and she said, "You’re kidding. That’s white trash food."

I lived in Wisconsin, and I shopped at the Pig. I spent my days living for Tim’s emails (by this time I’d finally admitted to myself that wife or no wife, I loved him), plotting ways to leave Wisconsin, and finding no way of doing it. I went back to school. This time, I got straight A’s. The only trouble was, I wasn’t sleeping.

Finally I went to my doctor and told her my problem. After much questioning, she decided that before she would prescribe anything, I had to promise to visit a therapist. A therapist?

My therapist was perfect as far as I was concerned. He was an old gay man from California who wore Birkenstocks and had a ready box of tissue every time my stories about my mother got to be too much. His sad green couch and I got to be great friends that summer. He’d nod, tell me that I had to change my behaviors or I’d never emerge from this (he gave it a name: generalized anxiety disorder), and I thought, I can’t believe how needy he makes me.

Then one day, he called and cancelled an appointment. It was as if the new guy I was dating had cancelled a dinner.

A few days later, I got a letter. We regret to inform you, the head doctor in the therapy group, that your doctor is indeed the doctor who was written about in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel’s expose.

What? I thought. I didn’t live in Milwaukee. I lived in Racine. I hadn’t read the article. So I marched my ass over to the library, found the article in question, and discovered that my goofy gay therapist was in reality an ex-priest who’d been defrocked after pleading guilty to having sex with a minor.

I’m not kidding.

Needless to say, I didn’t go back to him again. Those months became synonymous with the blackest times of my life, so forever after that, whenever I wanted to say that something was truly terrible, I’d say to myself, "It’s like Wisconsin."

And the next time that my depression hit, I used that story as my excuse not to go to therapy. That time, I can trace it to an actual cause: you see, that was the year that Tim died.

I can count on only a few fingers the men who’ve been important in my life. Not even they can compare to Tim. And I never even dated Tim. Insane, right?

He and I started out as email pals. Back in the day when the internet was still something that only people who were in the know could access, I joined a JD Salinger listserv. All the people on it were literary types like me who loved Salinger. Not just The Catcher in the Rye, but his other stories like "The Laughing Man" or "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" or "For Esme, With Love and Squalor," otherwise known in my head as the perfect short story.

Sometimes I think Tim thought he was Holden Caulfield. He was quick to jump on the phonies and he was as New York as it got. How to describe him? If you’ve ever watched Sex and the City, he was very like Steve, Miranda’s boyfriend. It was uncanny, really. He was just like him. I couldn’t watch the show withouth thinking of him, a Brooklyn boy trying to fit into Manhattan and finding that it just didn’t work.

The first time I met him, I’d been corresponding with him for probably five years. We had lunch and I went off and spent the rest of the day with Rich. I always brought other men with me when I went to see Tim. It was because he was in love with his wife and I was in love with him and I didn’t want him to know.

The next time I saw him, I brought Chris along with me. Chris didn’t like him. "He’s kind of weird," Chris told me. That’s just his meds, I explained. They’re not working. Tim, you see, was the king of mental illness. My blackest depression was only dipping its toe in the pond of what Tim fought every day. I worried about him constantly. I wondered if someone would tell me if something ever happened to him.

So I made friends with his wife. By then I’d moved to the city, and was teaching and working so hard that I’d convinced myself that my feelings for him were receding. I could be his friend and her friend and maybe find a way to move on. She and I would meet for coffee and she would try to convince me that she wasn’t the bad guy, that she was just trying to deal with a man whose moods were impossible.

The last time I saw him was the week before I went to Japan. He came out to Brooklyn because he couldn’t stand Manhattan a minute longer, he said. We went to brunch at this little French place that I loved. Then we took the train up to Greenwood Cemetery and stopped by his mother’s grave. Someone had bought the spot right next to it. He touched it. "Damn," he said. "There’s no place here for me."

Then we walked through Prospect Park and he said that he couldn’t stand his life as it was, that his meds were impossible and the headaches were getting worse, that his relationship with his wife was at the point where it wasn’t going to get any better. He said he had three friends and I was one of them. He said that he wanted to leave but didn’t know how. Perhaps he would move to the country. You’re talking like Holden Caulfield, I told him. Do you want a quarter so you can call Jane? That’s not funny, he said. I’ll never find a girl who keeps all her kings in the back row.

And all I could think was, you never even saw me, did you?

Then I went away to Japan. While I was there, I wrote this travelogue that I emailed to my friends and my students. Tim wrote to me: this is beautiful. You should publish this. He also said something about how he’s been messing around with encrypting his email and every word I ever wrote to him was safe. He wanted me to know that.

I can’t remember if I wrote him back. Yes, I did, because the next time I checked my email, there was a response from him. Then, two lines later, there was another email, from another friend, with Tim’s name in the subject.

Somehow, I knew what that email would say. But I didn’t click on it. I clicked on Tim’s email first. So I could pretend. I read it and reread it. It didn’t say anything, really.

Then I opened the other email. The same night Tim wrote me that email, he came home, sat down at his kitchen table to eat some dinner, and died. His wife found him the next morning, but it was too late.

I was in Japan. I couldn’t go to anyone and say, "Excuse me, but there’s a funeral tomorrow that I need to go to." Instead, I went up to my room, cried, and pretended nothing had happened. I made it through the remainder of the trip in a daze (strangely, this was when the John Denver’s head incident happened), and I’m certain that not a single person knew that I was grieving.

When I got back to Brooklyn, I called his wife and explained why I hadn’t been at the funeral. "That’s okay," she said. "But I need you to do me a favor." She’d had Tim cremated, she said, and needed to buy a plot. She knew that his mother was buried somewhere in Brooklyn and wanted me to help her find the place.

I told her I’d meet her at Atlantic Avenue and we could go to Greenwood together. New Yorkers, of course, don’t drive, so taking the train was the only reasonable option. She got off the train toting a giant Barneys New York shopping bag. "What’s in the bag?" I asked.

She kind of shrugged. "I didn’t know what else to do with him."

Good god, I thought. She has Tim in a Barney’s bag.

I couldn’t stop staring at it as we got on the train. It didn’t take long to get up to Greenwood, and the people there knew exactly what to do. It didn’t matter that the plot next to his mother was taken, they said. They could move the mother and then they’d be together.

I helped her pick out his urn and the spot they’d move him to. She said I could come to the interrment if I liked but I said no. That’s for family. Then we left.

A few weeks later, I met her for a movie. She wanted to go out and eat sushi, so we went to this place in midtown where I’d seen Miranda from Sex and the City eating once. There, she told me that she was having trouble with Tim’s life insurance. The autopsy showed that he had too many pills in his system, and they were saying that maybe he’d taken his own life.

I told her no. Definitely not. Not him. Never.

And yet. But I didn’t voice my doubts. I didn’t tell her about how he’d encrypted my emails and how he’d written me a note the night he died telling me how important I’d been to him. I didn’t tell her how he told me he couldn’t live with the things his body was doing to him anymore and how terrible their relationship made him feel. I didn’t tell her that, if I were checking off a list of warning signs for suicide, he probably fit every one.

I didn’t tell her any of that.

Now, if this were a movie, the next scene would show me and her getting through our grieving together, but in reality I couldn’t stand to be around her. No matter how much I’d loved him, supporting her was just too much for me.

I was weak.

And also, if this were a movie, I’d have spent the next few years memorializing him or something. But that’s not what I did. Instead, I jumped into my slut phase, dating multiple men at the same time, sleeping with half of them, and drinking far, far too much.

Other things happened. My dad got sick, my cousin died, my grandfather died, and I decided to move back to Chicago. A big part of my reason for being in New York was gone, you see. And then Chicago was even worse. I had a terrible job at a terrible school and terrible living conditions. I gained forty pounds in those two years. Good god, right?

The cloud is almost lifting. Sylvia Plath described it as a bell-jar: everything you see you see through a haze. I’m seeing far more clearly now than I was a year ago. I am.

I’m sad still, but hey. I’m still standing, right?

Sunday, February 10, 2008

Age Before Beauty

Age before beauty. My grandma used to say that to me all the time, right before she'd pick the best piece of whatever it was we were having. When you're old, she'd say, you can go first, too. This always seemed immensely unfair to me as a child because hey. Whatever it was, I wanted it.

However, now that I'm in my mid-thirties, I'm beginning to understand that Grandma was right: some good things come with age, and I have the right to want them. I've paid my dues.

So this weekend, I'm out at the bar with friends. They're all teachers who work with me, and one of them is rather young. She brings along a little friend, and he and I end up talking.

At some point in the evening, I begin to realize that this little boy is talking to me like I'm a romantic possibility for him, and what's more, he has no idea how old I am. Just how old does he think I am?

"About my age," he replies.

And how old is that?

"Twenty-five."

At this I have to laugh. Yeah, no. Guess again.

"Well, you're not thirty-five," he says, with a lot more superiority than he should, considering that he was totally wrong. I'm thirty-four.

The evening wears on, and he makes a few more comments that prove just how young he is, and I feel the need to taunt him. He's talking about tutoring former students, and I'm thinking he's young enough to be one of my former students. So I say, yes. I bet you like to tutor.

He takes a long look at me and says, "I can see now that you're older."

I'm surprised. Why is that?

"Because you're mean."

And of course I was. If there's one thing I've earned, it's being mean to men. They like it. And even if they don't like it, it amuses me. This one liked it.

So I'm at the gym last night relaying this story to my trainer, explaining how I've decided to tell everyone that I'm twenty-five from now on, and he says, "But he's not that far off. I mean, you're only a couple of years older than me."

I look at him. How old does he think I am?

"Thirty, tops," he says.

I laugh. Okay, I say. If that's what you want to believe, then I'm thirty.

"And anyway, what's wrong with a twenty-five year old?" he asks. I can tell he's a little miffed.

Everything.

"Age shouldn't matter," he insists. "You could meet someone younger and he could have a lot to say for himself. He could have experience. He could be well-traveled."

Yes, I supposed so, but I have experience, too. And I've been around a block or two thousand. I'm too jaded. No, I say. I'm not interested in educating any more boys.

"My ex was 39," he says.

And look how well that turned out.

"That wasn't because of her age. That's because she was crazy."

I didn't say that she'd have to be crazy to try that much of an age difference. I just shot him a sideways look.

Then he accused me of having hangups about age. (If that's my biggest hangup, I'll live with it.)

He then puts forth this theory that the older you are, the less age differences matter. Twenty-five and fifteen don't go together, but thirty-five and twenty-five do.

And hey. I'll give him that it's more acceptable, but I'm here to tell you something: he'd have to be one hell of a twenty-five-year-old for me to respect him. I want a man who's secure enough in himself to be able to tell me no, and I think that a younger man is less likely to do it. Because in all honesty, I can be a bit of a steamroller. If I want something, I usually find ways of getting it. And I hate being the one who decides everything. It's annoying. Call me with a plan. Don't call me and ask what I want to do. Yes, there's the sick, sad little secret: the master wants to be mastered.

And then, there's the games. The young ones are still all about the games. Me? Not so much. If you like me, call me. If you don't like me, don't call me. If you only sort of like me, don't call me. I don't want you to waste my time. But let's not jump through hoops. And let's not do evil things just to prove you can.

Are men my age immune to that? I don't know, probably not. Maybe I'm full of shit, and I should let the next kid who asks take me out. I just ... I want a grown-up. Is that so wrong? Maybe it's a sense of fairness, of meeting on an equal playing-field.

Don't get me wrong. I can see that there are good things about a long-term relationship with a younger man. Men tend to die first. If you find someone younger, perhaps you will. Then there's the sex. I don't want to stop after just once, and neither does he. Oh, and less boredom. He's less likely to spend the night in front of the tv.

So what do you think? Women, would you date someone young? Significantly younger -- say, more than five years? What do you prefer? Men, have you dated an older woman? Younger? Was there a difference? Same-sex couples, are the rules different if you're gay?

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

Numa Numa

Okay, I admit it: sometimes the stupid crap on the internet really cracks me up. Not too long ago, my friend Dawn introduced me to the Numa Numa guy.

Click on the picture to watch the video. He's fantastic.

Apparently, he's sparked a cult following. Witness this: a whole class singing and dancing to Numa Numa.

(What really cracks me up about this video is the guy in the back row trying to ignore them and get some work done. He reminds me of the roommate in the Chinese Backstreet Boys video.)

I, of course, couldn't leave this alone, and so did a little research online and found out that the real name for this song is "Dragostea Din Tei" and it's by a Rumanian band called O-Zone. Figures, right? A song this joyful/angry could only have come out of the Eastern Bloc, and only America could turn it into a cult hit.

So of course I found a video of the band performing it onstage, and it's almost better than the Numa Numa kid.

It's a Rumanian boy band! Who knew? (Actually, I could go for the guy in the black shirt. He looks all ... troubled and angry and happy. He's a little skinny and speaks Rumanian, but I'm sure we could get over our differences, yes?)

My real fascination with this video, however, is the Rumanian backup dancers. I mean, the song is very pop-influenced, but the dancers? They're dancing like gypsies! Gypsy pop-stars. Any moment, I expect one of them to pop into the crowd, lift a wallet or two, and then go back to dancing.

My fascination didn't end there. (Don't you dare laugh at me. You're reading about my fascination, so you can't laugh.) So of course I went looking for a translation of the lyrics and found this, from Wikipedia.com:

"Dragostea din tei" is written in Romanian, and the title is difficult to translate due to the lack of context for the phrase. There are several proposed translations of the title, such as Love out of the linden trees... Linden trees have strong lyrical associations in Romanian poetry, tied to the work of the poet Mihai Eminescu. Therefore the expression may be interpreted as romantic, "linden-type" love. A strong link may be to Eminescu's actual linden tree from Iasi, Copou park.

Another very likely translation takes into account the neighborhood "Tei" in Bucharest, the capital of Romania (in Romanian, "Cartierul Tei"). Since it's a place very popular with college students (several dorms in the area) and youngsters in general, the connection is there ("Love in Tei" as in "Love among young people"). In spring especially, many young pairs can be seen in the parks and streets in Tei, and "love is in the air" — even though it might be love that lasts just for a little while; the song alludes to this.

The third translation comes directly from a native Moldovan. He claims that the title uses a wordplay and simply means "Love at first sight", "dragostea dintâi", in Romanian (i.e. "Love from the linden trees", roughly analogous to "Love from the clear blue sky" in English, with the added associations that linden trees have in the Romanian language). This translation obviously rises above the literal meanings of the words and draws on something more poetic and specific to the language and culture. Given that O-Zone is from Moldova, where Romanian is spoken, it seems quite plausible that this interpretation is accurate. Furthermore, it provides something more universally meaningful, as the idea of love at first sight is understood more globally than the idea of love having to do with linden trees.

Don't you just love that there's somebody in this world who cares enough about a Rumanian pop song to have done this level of research? Of course, I found that research, so that makes me very nearly as bad. HOWever, I did not DO the research. I just googled it.

Well, I did a little research. Shut up. I had to, because now I needed to learn more about this poet, this Mihai Eminescu character. I read some of his poetry, and then I found it: the linden tree poem.

Desire

by Mihai Eminescu

Come now to the forest's spring

Running wrinkling over the stones,

To where lush and grassy furrows

Hide away in curving boughs.

Then you can run to my open arms,

Be held once more in my embrace,

I'll gently lift that veil of yours

To gaze again upon your face.

And then you can sit upon my knee,

We'll be all alone, alone there,

While the lime tree thrilled with rapture

Showers blossoms on your hair.

Your white brow with those golden curls

Will slowly draw near to be kissed,

Yielding as prey to my greedy mouth

Those sweet, red, cherry lips . . .

We'll dream only happy dreams

Echoed by wind's song in the trees,

The murmur of the lonely spring,

The caressing touch of the gentle breeze.

And drowsy with this harmony

Of a forest bowed deep as in prayer,

Lime-tree petals that hang above us

Will fall sifting higher and higher.

Figures. It's another damn man in love with a virgin, she of the white veil and white flowers and blah blah blah. Honestly. Purity is so overrated. Of course, this guy is fixated on her "lush and grassy furrows" and her "sweet cherry lips" which makes me think that her virgin state isn't going to last long.

Not to mix my fruit metaphors or anything.

But. Trust an Eastern European to find an image like the linden tree, which is also known (and I'm not sure why) as a lime tree in Rumania. Are they the same thing? I don't know anything about trees really. All I really know is that they're green. Until, of course, they turn brown. Like the virgin. Sorry, got off topic. Where was I?

Oh, yes. If you think about it, a lime is the perfect metaphor for love -- slightly sour, slightly sweet. Tangy. Adds a kick to everything. Yes. Limes. I get it.

So then, of course, after all that research, I did the only reasonable thing that a girl like me can do: I put the song on my iPod.